The global response to COVID-19 has seen varying degrees of lockdown and enforced isolation laws put in place by governments everywhere. However, while stay-at-home measures are safe for some, others could be at a higher risk of harm or, in extreme cases, being killed by a partner or family member. This article describes the heightened risk for women and girls in their homes during COVID-19 and provides advice policymakers can use to include women’s perspectives in decision making to ensure the protection of human rights.

Background of violence against women and girls on pandemic times.

The ‘Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action’ states that one of the main obstacles to achieve the objectives of equality, development and peace is gender-based violence (GBV), which violates and impairs the enjoyment of women’s human rights and fundamental freedoms. The vulnerability of those rights is worrying and must be addressed by all countries (UN Women, 2014, p.76).

In pandemic times, violence against women and girls increase significantly, especially when lockdown measures come into place to preserve the health of the population and prevent the spread of the outbreaks. Human Rights Watch (HRW) (2020) states, “Outbreaks of disease often have gendered impacts”. For example, the Ebola virus disease outbreak (2014) and the Zika virus (2015-2016) had particularly harmful impacts on women and girls and reinforced longstanding gender inequity (HRW, March 19, 2020).

Furthermore, certain vulnerabilities including biological, psychological or socio-cultural factors can exacerbate the effects of violence towards woman. Vulnerable groups include: girls, elderly, disabled, minority groups, indigenous, refugees, migrants, displaced, repatriated, rural or remote communities and women in conflict or civil wars (UN Women, 2014 p. 77).

Additional issues that can exacerbate the violence against women and girls are related to economic and social factors of the pandemic. As the United Nations Population Fund points out, “The economic effects of the Ebola outbreak led to exacerbated sexual exploitation risks for women and children” (UNPF, 2020). Aoláin argues that “the combination of pre-existing biological and socio-cultural factors means that while the health status of populations as a whole deteriorates during complex humanitarian crisis, women and children are especially vulnerable” (Aoláin, 2011 p.8). This was certainly the case during the Ebola outbreak, during which the violations of the fundamental rights of women that had the highest number of reports were sexual violence, domestic violence and aggression outside their communities (IRC, 2019 p.6).

Regarding global impact of the new virus, Human Rights Watch suggest that current reports indicate similar trends seen in Ebola and Zika (HRW 2020). In China for example, HRW argues that quarantine measures in China during the COVID-19 outbreak led to a rise in domestic violence, linked with lockdowns stress, cramped and difficult living conditions, or breakdowns in community support mechanisms. Women are simply unable to get away from abuse under lock-down conditions and unable to access services, especially when the perpetrator is at the same place.

The full impact on GBV during this crises is currently not known. Fraser (2020), suggests that in relation with violence against women, we can’t totally appreciate the full effects of GBV during pandemics. The four limitations are:

- limited data on changes in level of violence;

- lack of disaggregated data of vulnerable groups and gender (adolescent, older, refugee/migrant and disabled women)

- limited research on how outbreaks can exacerbate different forms of violence

- few documented examples of good practice in preventing and responding to GBV during an outbreak (p.5).

Gender-based violence in Australia.

Gender-based violence is more frequent than we think and the place of greatest occurrence is the victim´s home. According to the Women Health Organization (WHO), “As many as 70 per cent of women worldwide have experienced intimate partner physical and/or sexual violence in their lifetimes” (WHO, 2013). Stott states that “women usually experience violence and abuse at the hands of a men they know, often in their own homes, often repeatedly, and somethings over many years, if not a lifetime” (Stott, 2019 p.28).

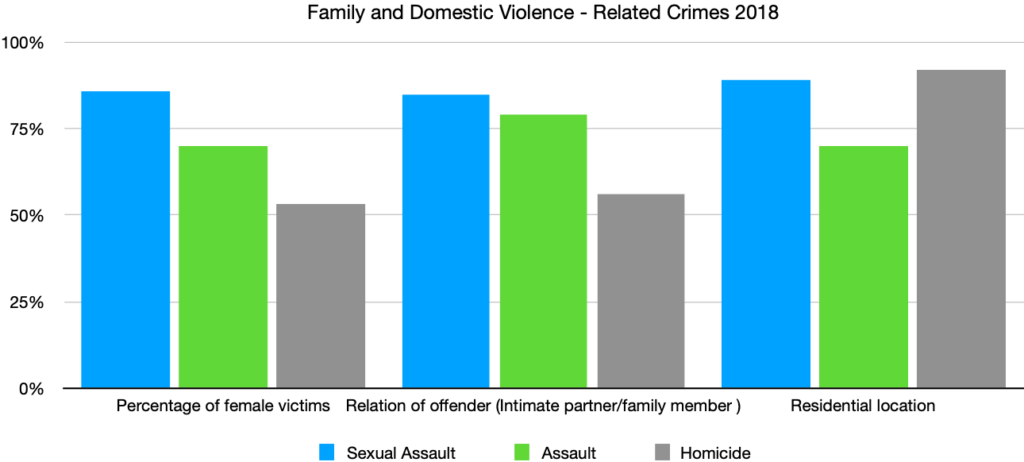

In the Australian case, the federal government in 2015 declared violence against women as a national crisis. Based on the data reported by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) in 2016, a third of all Australian women were assaulted physically. Moreover, a fifth of all women had experienced sexual harassment in the previous year (Piper & Stevenson, 2019). In relation to family and domestic violence (FDV), Piper and Stevenson emphasise that one women was murdered by an intimate partner each week in Australia and a third of all cases of homelessness are associated with violence within the family. According to ABS, two out of five assaults were FDV related, including serious assault resulting in injury and the majority of victims were women. The majority of perpetrators were intimate partners and the most common location was the home (ABS, 2018). A graphic representation of ABS findings can be seen in the Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Family and Domestic Violence- Related Crimes 2018

Note: The figure describes the data of Family and Domestic Violence related to Sexual Assault, Assault and Homicide on female gender in 2018 (ABS 2018).

Aboriginal communities have been found particularly vulnerable to FDV with higher frequency and severity. Additionally, some studies indicate a huge percentage of cases are unknown because survivors did not disclose them. In Queensland for example, an estimated 90% of violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander are unreported. The violence against women and girls has become normalised in indigenous communities and they tend to downplay the severity of the situation even when reporting it (Special Taskforce on domestic and family violence in Queensland, 2015 p. 120).

This data has to be considered in confinement measures in order to reduce the risk factors of violence for women living under the same roof with their offenders, paying special attention to vulnerable communities.

How to guarantee human rights of women and girls in COVID-19 outbreak.

As the 25th anniversary of the Beijing Platform for action on women’s rights and gender equality is approaching and the COVID-19 outbreak is affecting disproportionately women and girls, it is the duty of all states to protect women from the dire consequences that confinement can cause.

The data revealed globally confirms that preventing violence against women and girls has to be prioritised by government and non-government agencies, especially in times of pandemics. Following the UN Women (2020) proposal, government and non-government agencies must take gender perspective into account, putting women and girls at the front and centre of national plans in addressing violence against women and girls during and after the COVID-19 outbreak.

Plans to respond to the current outbreak must:

- work across agencies to prevent the exacerbation of violence against the female gender in times of crisis, especially in areas of lockdown or quarantine

- educate relevant agencies regarding the increased likelihood and severity of GBV cases during periods of partial or complete lock-down

- include women’s perspectives in pandemic planning and decision-making

- implement awareness campaigns of services available for victims of violence, especially in territories under confinement measures

- reassess previously reported cases of GBV where the aggressor lives under the same roof in light of pandemic lockdown measures

- strengthen victim support services during the COVID-19

In conclusion, national plans and policies should focus on both prevention and respond to women and girl victims of GBV. The pandemic and the consequent lockdown will, according to history, exacerbate the risk of domestic violence posed to vulnerable populations. The health system, social services, police, government and non-government entities have to provide specialised and effective support to victims of domestic violence before, during and after the COVID-19 outbreak. We have a responsibility to act to ensure the full guarantee of the human rights for all during times of crises, including the vulnerable.

References

Aolain, F. (2011) . Women, vulnerability, and humanitarian emergencies: Gender and Vulnerability in the Context of Humanitarian Crisis. Michigan Journal of Gender and Law: 18 (1), pp. 1–23. https://repository.law.umich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1011&context=mjgl.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2018). Recorded Crime- Victims. Report 2018. https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4510.0

Fraser, E. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic on Violence against Women and Girls: Methodology and Evidence gaps. VAWG Helpdesk Research. Report No. 284. http://www.sddirect.org.uk/media/1881/vawg-helpdesk-284-covid-19-and-vawg.pdf

Human Rights Watch – HRW. (2020). Human Rights Dimensions of COVID-19 Response: Address disproportionate impacts on women and girls. https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/03/19/human-rights-dimensions-covid-19-response#_Toc35446584.

International Rescue Committee (IRC). (2019). Everything on her shoulders. Rapid assessment on gender and violence against women and girls in the Ebola outbreak in Beni, DRC: Violence against Women and Girls. Report March 2019. https://www.rescue.org/sites/default/files/document/3593/genderandgbvfindingsduringevdresponseindrc-final8march2019.pdf.

Piper and Stevenson (2019). The long history of gender violence in Australia, and why it matters today. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/the-long-history-of-gender-violence-in-australia-and-why-it-matters-today-119927.

Special Taskforce on Domestic and Family Violence in Queensland. (2015). Not now, not ever: Putting and end to Domestic and family Violence in Queensland. Brisbane Department of Communities, Childs Safety and Disability Services. https://www.csyw.qld.gov.au/resources/campaign/end-violence/about/dfv-report-vol-one.pdf

Stott, N. (2019) On Violence: Gender and Vulnerability in the Context or Humanitarian Crisis. Carlton.

United Nations Population Fund – UNFPA (2020) As Pandemic Rages, Women and Girls face intensified risks: Risk of Violence, affected livelihoods. https://www.unfpa.org/news/pandemic-rages-women-and-girls-face-intensified-risks.

UN Women (2014). Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action: Beijing+5 Political Declaration and Outcome. https://beijing20.unwomen.org/~/media/headquarters/attachments/sections/csw/pfa_e_final_web.pdf#page=82

UN Women (2020). COVID 19: Women front and centre. https://unwomen.org.au/newsroom/media-releases/covid-19-women-front-and-centre/.

World Health Organization. (2013). Global and Regional Estimates of Violence against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence. London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and South African Medical Research Council. https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/violence/9789241564625/en/.

World Health Organization-WHO. (2020). Director-general´s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID 19. (2020, March, 11) https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19—11-march-2020.

Key words: COVID-19; Family and Domestic Violence Australia, Gender-Based Violence; Human rights, Violence against women and girls.

Biography

María del Pilar Correa Cortes, psychologist from Colombia with a Master’s degree in clinical, legal and forensic psychology from the Complutense University of Madrid. Over the past 17 years, she has been working as a psychologist in cases involving victims, who experienced all kind of violence inside and outside the armed conflict, especially women from mestizo, afro-descendant and indigenous communities in Colombia. In addition, she was a director of the Postgraduate programs in legal and forensic psychology in the Santo Tomas University in Colombia and currently a professor of undergraduate and postgraduate programs in psychology areas