The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development which was adopted by all UN Member states in 2015, called for urgent action for “people, planet and prosperity” (United Nations General Assembly 2015, p. 1). At the centre of the agenda was the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (United Nations 2023a). Each year, the UN puts out the Sustainable Development Goals Report, which presents an assessment of the SDGs, recognising the strength and direction of the goals that year (United Nations 2023b). Finland has been noted to be at the forefront of reaching a number of SDGs (United Nations 2022a) and currently “tops the global index” (Huynh 2023, p. 6). Following the Sustainable Development Report in 2022, Denmark, Sweden, and Norway ranked closely with their regional neighbour, being listed respectfully as second, third, and fourth in the report (United Nations 2022b). This article intends to investigate the Nordic countries’ current successful progress towards reaching the Sustainable Development Goals and the 2030 Agenda, and how the different countries work nationally to achieve the goals. It will be argued that the backbone of their successful national implementation process is their stable political systems which rests on the Nordic model and social democracy. This indicates that many practices necessary for the successful implementation already existed and were culturally imbedded in the countries policies prior to the introduction of the SDGs, giving them a “head start” in achieving the goals.

The Nordic success story

The Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden) have indeed been ranked highly in international measures of how far they have come in implementing SDGs on the national level (Nordic Council of Ministers 2021, p. 3). The Nordic countries have taken significant steps with several goals, including:

- SDG1 (No Poverty)

- SDG3 (Good Health and Well-Being)

- SDG4 (Quality Education)

- SDG5 (Gender Equality)

- SDG7 (Affordable and Clean Energy)

- SDG8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth)

- SDG10 (Reduced Inequalities), and

- SDG16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions).

That being said, the Nordic countries have not yet achieved sustainable development, and are especially challenged “by unsustainable consumption and production, climate change, and the biodiversity crisis” (Nordic Council of Ministers 2021, p. 3). The positive progress seen in a number of these goals has been taken note of, for instance through the SDG Index Ranking (Sachs et al. 2023, p. 25).

The Nordic Model

The Nordic countries share a range of similarities. The countries are all relatively small, both in size and population, culturally homogenous, and have relatively high GDPs (Ervasti 2008: 3). The countries share a strong commitment towards social investment and public services. It is from these social and economic policies that the regional model called “the Nordic Model” grew. This is a concept used to describe the features of the economic and social welfare systems that are used by the Nordic countries (Ervasti 2008: 3). The two pillars of this model are the welfare state and labour market relations. Another common feature of the Nordic countries is their social democratic political systems. The state and government in these countries have had reputations of being vehicles for the working class and higher classes alike to promote their interests (Ervasti 2008: 4). This has created a more trusting relationship between individuals of varying financial backgrounds and the state. ‘Equality’ and ‘cooperation’ are keywords for Nordic policies and labour markets alike (Pedersen and Kuhnle 2017, p. 251), and one may wonder if these features promote the SDG progress seen in the Nordic countries.

The Nordic SDG progress may be linked to strong regulations, institutions and policies. Low levels of income inequality, represented through SDG10 (Reduced Inequality) have been achieved through robust social welfare programs, funded by progressive tax systems and implemented alongside policies that ensure that wealth is distributed more evenly among the population (Nordic Council of Ministers 2021, p. 3). Looking at SDG16 (Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions), the Nordic countries are also reputed to have strong democratic institutions with high levels of trust in government and low levels of corruption (Pedersen and Kuhnle 2017, p. 250). The countries are, further, known for their contribution towards peace and security through diplomatic missions and peacekeeping (Archer 1996, p. 457; Nordic Council of Ministers 2019, p. 9). These examples exert a possible link between the political systems of the Nordic countries and their success in implementing SDGs at their national levels.

The national implementation strategies

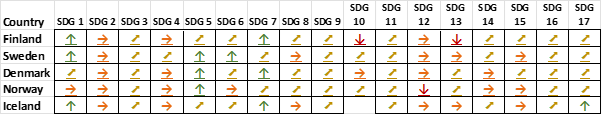

Figure 1

Sachs et al. 2023

Figure 1 shows each country’s trend for implementing the individual SDGs. The green arrow indicates the country being on track or maintaining achievement, the yellow arrow indicates a moderate increase, the orange arrow indicates stagnation, and the red arrow indicates a decrease. No arrow means insufficient data.

The organisation of the national implementation of SDGs is closely linked to the government in all five countries. The work that is being undertaken to implement the SDGs is highly based on policies that were already in place prior to the commitment. Various responsibilities have, however, been delegated subsequently:

In Denmark, the work is led by the government and the parliament, where various Ministries (such as the Ministries of Foreign Affairs and Environment) have responsibilities for the individual goals and targets within their respective areas of administration (Nordic Council of Ministers 2021, p. 8). There has also been set up an advisory panel for the 2030 Agenda, made up of representatives from the research community, business sector and civil society. Various mediums and projects (e.g. Global Goals Week) have been set up to share and communicate knowledge about the SDGs to the public, where progress and solutions to challenges can be raised and discussed (Nordic Council of Ministers 2021, p. 10).

The Finnish organisation focuses on how both government and society have a common responsibility to implement SDGs. Once per election term, the government reports on the Finnish sustainable development process to the parliament. Whilst the government and Prime Minister’s Office lead the process, various forums and networks support the work towards the 2030 Agenda. One of these forums is the Finnish National Commission on Sustainable Development, whose tasks include monitoring the global agenda and speeding up the implementation process (Nordic Council of Ministers 2021, p. 12). The Commission is followed by two expert panels: The Expert Panel for Sustainable Development includes the voices of internationally renowned experts and academics, and the Finnish 2030 Agenda Youth Group includes 20 people between the ages of 15-28 that represent Finland geographically and socially. The aim is to engage a variety of Finnish people and give them a chance to participate in the process (Nordic Council of Ministers 2021, p. 13), with the conviction that societal dedication and commitment to sustainable development is key (Nordic Council of Ministers 2021, p. 15).

In Iceland, there has been a focus on integrating the SDGs into national fiscal plans that are updated every five years. The government has found that 65 of the 169 targets are particularly relevant for Iceland and these goals will guide the work on implementing the 2030 Agenda (Nordic Council of Ministers 2021, p. 17). It is the Government’s Inter-ministerial Working Group on the 2030 Agenda that coordinates the SDGs and 2030 Agenda in the country. Since 2021, Iceland has conveyed an annual national status report on the implementation process in addition to regular reports sent to the UN (Nordic Council of Ministers 2021, p. 18). The government, further, appointed a committee to more efficiently spread information about the SDGs, involve civil society, and coordinate work between local and national levels (Nordic Council of Ministers 2021, p. 19). Surveys have shown a more than 30% increase in awareness of the SDGs in Iceland between 2018 and 2020 (Heimsmarkmidin 2023).

The responsibility for the national implementation of the 2030 Agenda in Norway is allocated to different ministries and their departments (depending on their respective areas of administration). The process is regulated by the budget that each ministry receives (Nordic Council of Ministers 2021, p. 23). Since 2020, Norway has had a minister for Sustainable Development who is responsible for coordinating implementation (Kommunal- og moderniseringsdepartementet 2020). As with the other Nordic countries, Norway regularly reports on the implementation of SDGs and sends in voluntary national reviews to the UN (Nordic Council of Ministers 2021, p. 23). The government aims to promote consensus amongst Norwegians in the policies that are related to the SDGs and has, thus, held a biannual Forum for Consensus Politics since 2018 (Utenriksdepartementet 2018). The forum has representatives from a broad spectrum of civil society, from academia to NGOs and the private sector (Nordic Council of Ministers 2021, p. 24). Increased local awareness is also achieved by spreading information during events, such as the international football tournament, Norway Cup (Norway Cup 2022).

Lastly, Sweden bases its implementation process on delegated responsibility. All national agencies, ministries and departments have respective areas of responsibility. A national coordinator for the 2030 Agenda has been appointed to support the government’s work and help promote and strengthen the work that the various responsible actors do (Nordic Council of Ministers 2021, p. 29). The coordinator presents the work that currently takes place to reach the goals and also gets the perspectives and participation of youths (Nordic Council of Ministers 2021, p. 27). The government attempts to increase transparency surrounding the goals and the 2030 Agenda by submitting reports to the parliament at least once per term. These reports include the progress that is made and ensure continued systematic dialogue between the parliament and government on the 2030 Agenda (Nordic Council of Ministers 2021, p. 28). Civil society organisations create reports, spread information about the country’s progress, and maintain dialogue with the Swedish government on their work on the 2030 Agenda (Concord 2021, p. 6).

Australian implementation

Compared to the Nordic countries, Australia has a larger and more widespread population. The Nordics and Australia are similar in that they are all democratic states. The Australian Government sent in a Voluntary National Review on the implementation of SDGs in 2018 (Australian Government 2018). In 2020, Monash University noted that whilst all the main Australian political parties support the SDGs, there was a lack of implementation agenda for achieving the goals (Monash University 2020).

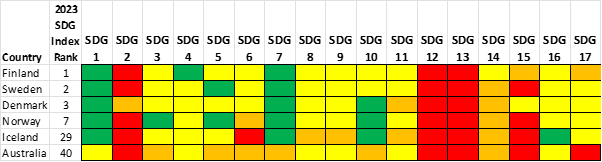

Figure 2

Sachs et al. 2023

Figure 2 shows the current overall goal results for the Nordics and Australia. Green represents goal achievement, yellow represents that challenges remain, orange represents significant challenges, and red represents major challenges.

Through Figure 2, one can see that the Nordic countries, overall, have gotten further in achieving the SDGs than Australia. This could be because the Nordic policies and political systems already had aspects of the SDGs culturally embedded in them, through the Nordic Model. As mentioned, Nordic countries have a long history of high standards of living, strong education systems and generally robust social welfare/tax systems, which might make it seem natural that they score as high as they do. It appears the Nordic states had to have fewer turnarounds due to their existing systems already backing many aspects of the SDGs. This supports the article’s original claim that the backbone of their successful national implementation process is their stable political systems which rests on the Nordic model and social democracy.

Conclusion

Based on the strategies led by the Nordic countries, it seems fair to claim that the success of implementing SDGs in a country is partly dependent on effective government arrangements, and that these arrangements are present in these five social democratic political systems. The Nordic countries have a high level of political stability, which provides an environment for policy continuity and long-term planning, as well as strong institutions that promote transparency and accountability in governance so that their progress towards the SDGs can be monitored and evaluated effectively. The latter can be seen through their 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which reviews their “national political structures for implementing the 2030 Agenda” (Nordic Council of Ministers 2021, p. 3). The countries’ robust welfare systems further help address social and economic issues and inequalities, which are central to the SDGs. Finally, the populations put social pressure on the commitment the governments have placed on SDGs, perhaps due to the high education systems that promote awareness and understanding of the Goals among the citizens. Where the Nordic countries’ progress towards the SDGs might also be linked to factors that are external to their political systems, such as their low population density, large areas of unspoilt natural environment, and high GDP, it seems unlikely that their progress is fully unrelated to the characteristics of the Nordic Model and their social democratic political systems. States struggling with the implementation of SDGs could, therefore, seemingly take inspiration from the Nordic Model.

About the Author

Elisabeth Haugland Austrheim is a PhD candidate at the University of Queensland. Her current study focuses on the drivers of protracted armed conflicts in the post-WW2 era. With a background in comparative politics, international relations, and peace and conflict studies, Elisabeth seeks to gain a deeper understanding of contemporary armed conflicts and why some of them last so much longer than the average armed conflict.

References

Archer, C. (1996), ‘The Nordic Area as a “Zone of Peace”’, Journal of Peace Research 33(4), p. 451-467.

Australian Government (2018), ‘Report on the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals’, https://www.sdgdata.gov.au/about/voluntary-national-review, accessed 12.10.23.

Concord (2021), ‘Civil Society Spotlight Report on Sweden’s Implementation of the 2030 Agenda, Recommendations and Review of Actions Taken Ahead of High-level Political Forum 2021’, Stockholm: Concord Sweden.

Ervasti, H. (2008), ‘Nordic Social Attitudes in a European Perspective’, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

Hagemann, A. and Bramsen, I. (2019), ‘New Nordic Peace, Nordic Peace and Conflict Resolution Efforts’, TemaNord 2019(524), p. 1-55.

Heimsmarkmidin (2023), ‘PR and communications’, https://www.heimsmarkmidin.is/default.aspx?pageid=72c09d14-c1a3-484d-bdda-f168798525f4, accessed 03.10.23.

Huynh, D. N (2023), ‘The Nordic Region and the 2030 Agenda: Governance and engagement (2021-2022)’, Nordregio Report 2023(4), p. 1-47.

Kommunal- og moderniseringsdepartementet (2020), ‘Nikolai Astrup blir bærekraftsminister’, https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumentarkiv/regjeringen-solberg/aktuelt-regjeringen-solberg/kmd/pressemeldinger/2020/nikolai-astrup-blir-barekraftsminister/id2685430/, accessed 03.10.23.

Monash University (2020), ‘Australia Lags on UN Targets for a More Prosperous, Greener, Fairer Nation, Monash Report Shows’, https://www.monash.edu/news/articles/australia-lags-on-un-targets-for-a-more-prosperous,-greener,-fairer-nation,-monash-report-shows, Accessed 12.10.23.

Nordic Council of Ministers (2021), ‘The Nordic Region and the 2030 Agenda’, http://doi.org/10.6027/nord2021-042, accessed 28.09.23.

Norway Cup (2023), ‘Norway Cup Global Goals’, https://norwaycup.no/global-goals/, accessed 03.10.23.

Pedersen, A. W. and Kuhnle, S. (2017) ‘The Nordic welfare state model: 1 Introduction: The concept of a “Nordic model”’, in I. O. P. Knutsen ed. The Nordic Models in Political Science: Challenged, but Still Viable? (pp. 249-272). Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

Sachs, J. D., Lafortune, G., Fuller, G., and Drumm, E. (2023), ‘Sustainable Development Report 2023, Implementing the SDG Stimulus’, Dublin: Dublin University Press.

United Nations (2022a), ‘Finland’, https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/memberstates/finland, accessed 27.09.23.

United Nations (2022b), ‘The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022’, New York: United Nations Publications.

United Nations (2023a), ‘The 17 Goals’, https://sdgs.un.org/goals, accessed 26/09.23.

United Nations (2023b), ‘The Sustainable Development Goals Report Special Edition’, New York: United Nations Publications.

United Nations General Assembly (2015), ‘Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015’, A/RES/70/1. United Nations, New York.

Utenriksdepartementet (2018), ‘Nytt forum skal bidra til samstemthet’, https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumentarkiv/regjeringen-solberg/aktuelt-regjeringen-solberg/ud/nyheter/2018/nytt-forum-skal-bidra-til-samstemthet/id2602703/, accessed 03.10.23.